[This obituary was written by my aunt Jill, about her husband George. It was submitted to The Guardian but it was shortened for publication. Published version.]

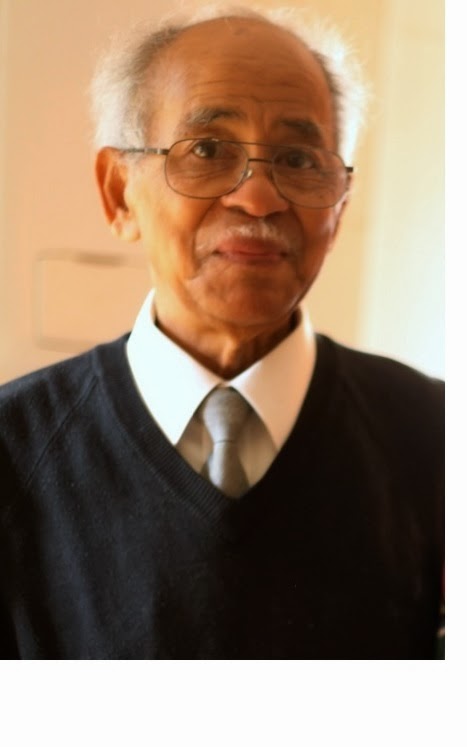

GEORGE POWE

My

husband, Oswald George Powe, always known as George, was born in Kingston Jamaica

in 1926. He had a happy childhood in a family with high aspirations for its

children. His father was a Chinese conjuror, from Canton,

China, who emigrated to Jamaica and became a

merchant, along with his brothers. George’s parents made sure that he

had a good education and he was part way through college, studying to become an

electrical engineer when he volunteered, in 1944, to join the Royal Air Force.

Trained in radar, he spent much of the time stationed in Devon and Cornwall. He went back to

Jamaica a couple of years

after the war ended, and was demobbed, but decided to returned to England

within a few months. He stayed here for the rest of his life.

In

the 40’s he was very aware that there

was widespread racial discrimination in the forces and in the civilian world.

He saw horrific treatment of black people in London, was on the receiving end of much

of it, and was soon fighting to attempt

to turn this situation around. He joined the Communist Party, which at that

time was probably the most active group promoting the rights of disadvantaged

and exploited people. At some point in

the 40’s he wrote a pamphlet called

“Don’t Blame the Blacks”.

He

moved to Birmingham

and later to Long Eaton, Derbyshire. He eventually left the Communist Party and

joined the Labour Party, retaining his Labour Party membership for the rest of

his life. In the early 60’s he was elected as a Labour Party Councillor in

Long Eaton, and was, I believe, the first black man to achieve such a

position in this country. He moved to Nottingham

in 1971 and after a few years was elected, again as a Labour Councillor, on

Nottinghamshire County Council.

I

first met him just over 50 years ago, shortly after Cuba Crisis Week. We were

pushing leaflets about the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament through letterboxes on opposite sides of a

road on a snowy evening. I remember thinking that he must have been feeling

very cold, as I assumed he had just arrived in this country after a long

journey in a boat.

Little

did I know that he had been over here for 20 years!

In

the 60’s black people were still being

treated very badly in public places such as pubs, clubs, schools, shops and in

courts of law. He and I started a

campaign against a Nottingham pub where black

people were not welcomed in the same room as whites. A large number of people,

black and white came along to try to be

served and then stay there as long as they could, drinking very slowly indeed,

in order to make it a bad night for the pub’s profits. I ordered two half pints

of bitter, and was about to be served when the landlady realised that one of

them was for George. She said “ I’ll serve an Indian or a Pakistani but not one

of those black…………..” She snatched the

beer back and we were unable to get a drink. It began to turn a bit nasty, and

at one point a glass of beer was emptied over the bar, but we all left peacefully.

The pub was closed down a few weeks later.

Thankfully

over the years such direct action became less necessary, and more Black and

Asian people started to become active in

local and international politics, many

of them joining the Labour Party, with some involved in smaller and more hard-line

groups.

George

always spent part of his spare time in strictly political campaigns. He devoted

just as much time in assisting individual people to gain the treatment they

were entitled to expect from the police, the education system, and in their

places of work. Although the majority of these people were from Jamaica and the wider Caribbean, India, Pakistan

or Africa, he was also instrumental in

assisting many white people to gain their rights.

He

was the prime founder member of the Afro-Caribbean Centre (ACNA), formed in 1971 by a number of black organisations, eventually securing

permanent premises in Hungerhill

Road, Nottingham,

opening as a community centre and social club in 1978. He acted as Company

Secretary until few years ago, and was an

active Director until he died. The ACNA Centre stands as part of his legacy.

When

British Governments passed various Immigration Acts, it was clear that many

people would need help in dealing with all the problems they caused. Hundreds,

possibly thousands, of people have been helped by him to resist this new type of discrimination. Whenever a

Jamaican had a relative who was refused a visa to come to Britain, and came to George for

help, just as long as he knew they were telling him the truth about their circumstances, he would

advise them about any grounds on which they could appeal. I cannot remember a time when any of these

cases which went to appeal with his help were turned down.

I

am proud to have been married to a man who was so generous with his time, and

who fought hard for the rights of all communities. He had both Jamaican

and British citizenship, and could move

freely and successfully in both societies. I went to Jamaica with him four times over

the past thirty years. To see the respect he was afforded when in Jamaica was

amazing. So many people in Spanish Town, Kingston and

beyond knew him, and those who didn’t would never guess from the way he walked

and talked, spoke and listened, that during his life he had so spent much more

time in England than he

did in Jamaica. Wherever he went people

treated him in line with one of his favourite expressions – respect and

dignity.

He

was not a religious man, but he had strong moral compass. He never forgot his roots. It was a privilege

to be part of his life.

Jill

Westby September 24, 2013

He died on September

9, 2013. He is survived by his second wife, Jill, whom he married in 1982;

4 children, 3

grandchildren and 2 great-grandchildren from his first marriage to Barbara

Florence Poole in 1949; and 4 grandchildren and 4 great-grandchildren from a

previous relationship with Lilian Elisabeth Willis during the time he was

stationed in Devon.